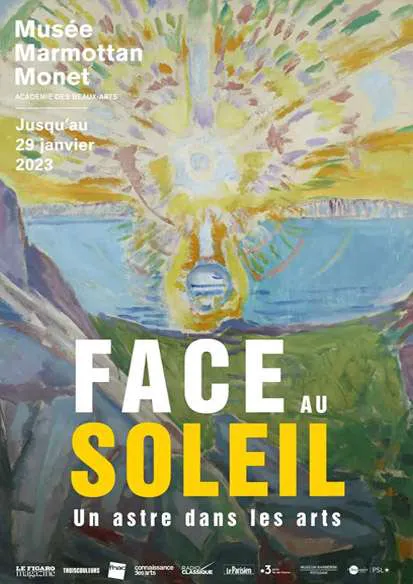

On 13 November 1872, from the window of his hotel room in Le Havre, Claude Monet painted a view of the port in the dawn mist. Exhibited two years later under the title Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), the work inspired art critic Louis Leroy to coin the term “Impressionism”, thus creating a name for the artists’ group formed by Monet and his friends. In 2022, the Musée Marmottan Monet is celebrating the 150th anniversary of this centrepiece of its collections, paying tribute to it via the exhibition Face au Soleil, un astre dans les arts (Facing the Sun: the Celestial Body in the Arts).

Thanks to 53 loaners, this exhibition features some 100 works in total, retracing the history of the representation of the Sun, from antiquity to the present. A rare ensemble of drawings, paintings, photographs and measuring instruments from the Paris Observatory illustrates the developments in astronomy down the centuries, reflecting also the evolution of landscape and atmospheric painting.

From the Sun Gods of antiquity to mythological themes, the Sun was adopted as a symbol by the greatest sovereigns, notably France’s so-called Sun King, Louis XIV. But the Sun also fascinated scientists, of course. Copernicus, in demonstrating that the Earth turned on its own axis and around the Sun (rather than the opposite, as previously thought) started a revolution that would influence the arts. The desire to represent the world as it truly is was taken up by painters who focused on and developed landscape art. The theme of nature depicted at sunrise or sunset held a particular fascination. Works by Peter-Paul Rubens, Claude Gellée (or Lorrain), William Turner, Caspar David Friedrich, Gustave Courbet and Eugène Boudin retrace this development, while Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant was a landmark piece.

The period 1880-1914 marked a new stage. Alongside astronomy (a science of observation), astrophysics evolved, making it possible to study the physical nature of celestial objects. Such major scientific developments, widely reported in the press at the time, allowed people to learn much more about the Sun, including its chemical composition. The Sun became an object of study in itself, and a theme in itself for artists. They might no longer paint a landscape with our star making its presence felt from afar, but instead focus on the Sun with greater intensity. Each artistic movement created its own special vision of our star: naturalist and harmonious among Nordic painters like Valdemar Schønheyder Møller, Laurits Tuxen and Anna Ancher; symbolist for Félix Vallotton; poetic for fauvist André Derain; orphist for Delaunay; futurist for Wladimir Baranov-Rossiné; and expressionist or even tragic for Albert Trachsel, Otto Dix or Edvard Munch…

Around 1920, a further revolution occurred with Einstein’s theory of general relativity, establishing that the universe is constantly expanding. The science altered artists’ visions of the Sun. Miró’s poetic constellations and Calder’s Stabiles conveyed this dilation of space. In the ceaselessly growing vastness, our Sun became just another modest star, still dazzling for Richard Warren Poussette-Dart, but destined to disappear for Piene. Gérard Fromanger’s Impression soleil levant, 2019 continues in this vein, reinterpreting, from outer space, the viewpoint offered up by Monet 150 years ago, and closing the exhibition Facing the Sun: the Celestial Body in the arts.

Practical informations

21st sept. 2022 - 29th jan. 2023

Musée Marmottan Monet

2 rue Louis Boilly75016 Paris Tel. : +33 (0)1 44 96 50 33

Practical informations

21st sept. 2022 - 29th jan. 2023

Musée Marmottan Monet

2 rue Louis Boilly75016 Paris Tel. : +33 (0)1 44 96 50 33